- 著者

- フェルディナンド・グレゴロヴィウス

- 初版

- 1874年

- 翻訳

- John Leslie Garner

- 引用サイト

- The Project Gutenberg

Chapter XX: Negotiations with the House of Este

The hereditary Prince of Ferrara made a determined resistance before yielding to his father's pressure, but the latter was now so anxious for the marriage to take place that he told his son that, if he persisted in his refusal, he would be compelled to marry Lucretia himself. After the duke had overcome his son's pride and secured his consent, he regarded the marriage merely as an advantageous piece of statecraft. He sold the honor of his house at the highest price obtainable. The Pope's agents in Ferrara, frightened by Ercole's demands, sent Ramondo Remolini to Rome to submit them to Alexander, who sought the intervention of the King of France to secure more favorable terms from the duke. A letter from the Ferrarese ambassador to France to his master throws a bright light on this transaction.

My Illustrious Master: Yesterday the Pope's envoy told me that his Holiness had written him about the messenger your Excellency had sent him demanding two hundred thousand ducats, the remission of the annual tribute, the granting of the jus patronatus for the bishopric of Ferrara, by decree of the consistory, and certain other concessions. He told me that the Pope had offered a hundred thousand, and as to the rest—your Excellency should trust to him, for he would grant them in time and would advance the interests of the house of Este so that everyone would see how high in his favor it stood. In addition, he told me that he was instructed to ask his most Christian Majesty to write to the illustrious cardinal to advise your Excellency to agree. As your Excellency's devoted servant I mention this, although it is superfluous; for if this marriage is to take place, you will arrange it in such a way that "much promising and little fulfillment" will not cause you to regret it. I informed your Excellency in an earlier letter how his most Christian Majesty had told me that his wishes in this affair were the same as your own, and that if the marriage was to be brought about, you might derive as

much profit from it as possible, and if it was not to take place, his Majesty stood ready to give Don Alfonso the lady whom your Excellency might select for him in France.

Your ducal Excellency's servant,

Bartolomeo Cavaleri.

Lyons, August 7, 1501.

Alexander did not wish to send his daughter to Ferrara with empty hands, but the portion which Ercole demanded was not a modest one. It was larger than Blanca Sforza had brought the Emperor Maximilian; moreover, one of the duke's demands involved an infraction of the canon law, for, in addition to the large sum of money, he insisted upon the remission of the yearly tribute paid the Church by the fief of Ferrara, the cession of Cento and Pieve, cities which belonged to the archbishopric of Bologna, and even on the relinquishment of Porto Cesenatico and a large number of benefices in favor of the house of Este. They wrangled violently, but so great was the Pope's desire to secure the ducal throne of Ferrara for his daughter that he soon announced that he would practically agree to Ercole's demands, which Caesar urged him to do.

Cavallieri to Ercole, Lyons, August 8, 1501. The Pope has written his nuncio that he agreed to the duke's demands, for the purpose of concluding the marriage, which would be extraordinarily advantageous to himself and the Duke of Romagna.

Nor was Lucretia herself less urgent in begging her father to consent; she was the duke's most able advocate in Rome, and Ercole knew that it was due largely to her skilful pleading that he succeeded in carrying his point.

The negotiations took this favorable turn about the end of July or the beginning of August, and the earliest of the duke's letters to Lucretia and the Pope, among those preserved in the archives of the house of Este, belong to this period.

August 6th Ercole wrote his future daughter-in-law, recommending to her for her agent one Agostino Huet (a secretary of Caesar's), who had shown the greatest interest in conducting the negotiations.

August 10th he reported to the Pope the result of the conferences which had taken place, and urged him not to look on his demands as unreasonable. This he repeated in a letter dated August 21st, in which he stated in plain, commercial terms that the price was low enough; in fact, that it was merely nominal.

In the meantime the projected marriage had become known to the world, and was the subject of diplomatic consideration, for the strengthening of the papacy was agreeable to neither the Powers of Italy nor those beyond the peninsula. Florence and Bologna, which Caesar coveted were frightened; the Republic of Venice, which was in constant friction with Ferrara, and which had designs upon the coast of Romagna, did not conceal her annoyance, and she ascribed the whole thing to Caesar's ambition.

Despatches of the Ferrarese ambassador, Bartolomeo Cartari, from Venice, June 25, July 28, and August 2, 1501. Archives of Modena.

The King of France put a good face upon the matter, as did also the King of Spain; but Maximilian was so opposed to the marriage that he endeavored to prevent it. Ferrara was just beginning to acquire the political importance which Florence had possessed in the time of Lorenzo de' Medici, consequently its influence was such that the German emperor could not be indifferent to an alliance between it and the papacy and France. Moreover, Bianca Sforza was Maximilian's wife, and at the German court there were other members and retainers of the overthrown house—all bitter enemies of the Borgias.

In August the Emperor despatched letters to Ferrara in which he warned Ercole against any marital alliance between his house and that of Alexander. This warning of Maximilian's must have been highly acceptable to the duke, as he could use it to force the Pope to accede to his demands. He mentioned the letter to his Holiness, but assured him that his determination would remain unshaken. Then he instructed his counselor, Gianluca Pozzi, to answer the Emperor's letter.

Ercole's letter to Pozzi in Ferrara, August 25, 1501. Maximilian's letters are not in the Este archives but in Vienna.

Ercole's letter to his chancellor is dated August 25th, but before its contents became known in Rome the Pope hastened to agree to the duke's conditions, and to have the marriage contract executed. This was done in the Vatican, August 26, 1501.

The instrument was drawn by Beneimbene.

He immediately despatched Cardinal Ferrari to Ercole with the contract, whereupon Don Ramiro Remolini and other proxies hastened to Ferrara,

Cardinal Ferrari to Ercole, Rome, August 27, 1501.

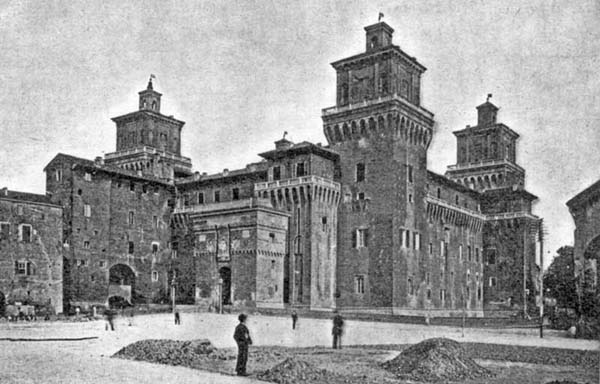

where, in the castle of Belfiore, the nuptial contract was concluded ad verba, September 1, 1501.

On the same day the duke wrote Lucretia, saying that, while he hitherto had loved her on account of her virtues and on account of the Pope and her brother Caesar, he now loved her more as a daughter. In the same tone he wrote to Alexander himself, informing him that the betrothal had taken place, and thanking him for bestowing the dignity of Archpriest of S. Peter's on his son, Cardinal Ippolito.

Ducal Records, September 1, 1501.

Less diplomatic was Ercole's letter to the Marchese Gonzaga informing him of the event. It clearly shows what was his real opinion, and he tries to excuse himself for consenting by saying he was forced to take the step.

Illustrious Sir and Dearest Brother: We have informed your Majesty that we have recently decided—owing to practical considerations—to consent to an alliance between our house and that of his Holiness—the marriage of our eldest son, Alfonso, and the illustrious lady Lucretia Borgia, sister of the illustrious Duke of Romagna and Valentinois, chiefly because we were urged to consent by his Most Christian Majesty, and on condition that his Holiness would agree to everything stipulated in the marriage contract. Subsequently his Holiness and ourselves came to an agreement, and the Most Christian King persistently urged us to execute the contract. This was done to-day in God's name, and with the assistance of the (French) ambassador and the proxies of his Holiness, who were present; and it was also published this morning. I hasten to inform your Majesty of the event because our mutual relations and love require that you should be made acquainted with everything which concerns us—and so we offer ourselves to do your pleasure.

Ferrara, September 2, 1501.

The letter is reproduced in Zucchetti's Lucrezia Borgia, Duchessa di Ferrara, Milan, 1869.

September 4th a courier brought the news that the nuptial contract had been signed in Ferrara. Alexander immediately had the Vatican illuminated and the cannon of Castle S. Angelo announce the glad tidings. All Rome resounded with the jubilations of the retainers of the house of Borgia.

This moment was the turning point in Lucretia's life. If her soul harbored any ambition and yearning for worldly greatness, what must she now have felt when the opportunity to ascend the princely throne of one of Italy's oldest houses was offered her! If she had any regret and loathing for what had surrounded her in Rome, and if longings for a better life were stronger in her than were these vain desires, there was now held out to her the promise of a haven of rest. She was to become the wife of a prince famous, not for grace and culture, but for his good sense and earnestness. She had seen him once in Rome, in her early youth, when she was Sforza's betrothed. No sacrifice would be too great for her if it would wipe out the remembrance of the nine years which had followed that day. The victory she had now won by the shameful complaisance of the house of Este was associated with deep humiliation, for she knew that Alfonso had condescended to accept her hand only after long urging and under threats. A bold, intriguing woman might overcome this feeling of humiliation by summoning up the consciousness of her genius and her charm; while one less strong, but endowed with beauty and sweetness, might be fascinated by the idea of disarming a hostile husband with the magic of her personality. The question, however, whether any honor accrued to her by marrying a man against his will, or whether under such circumstances a high-minded woman would not have scornfully refused, would probably never arise in the mind of such a light-headed woman as Lucretia certainly was, and if it did in her case, Caesar and her father would never have allowed her to give voice to any such undiplomatic scruples. We can discover no trace of moral pride in her; all we discern is a childishly naive joy at her prospective happiness.

The Roman populace saw her, accompanied by three hundred knights and four bishops, pass along the city streets, September 5th, on her way to S. Maria del Popolo to offer prayers of thanksgiving. Following a curious custom of the day, which shows Folly and Wisdom side by side, just as we find them in Calderon's and Shakespeare's dramas, Lucretia presented the costly robe which she wore when she offered up her prayer, to one of her court fools, and the clown ran merrily through the streets of Rome, bawling out, "Long live the illustrious Duchess of Ferrara! Long live Pope Alexander!" With noisy demonstrations the Borgias and their retainers celebrated the great event.

Alexander summoned a consistory, as though this family affair were an important Church matter. With childish loquacity he extolled Duke Ercole, pronouncing him the greatest and wisest of the princes of Italy; he described Don Alfonso as a handsomer and greater man than his son Caesar, adding that his former wife was a sister-in-law of the Emperor. Ferrara was a fortunate State, and the house of Este an ancient one; a marriage train of great princes was shortly to come to Rome to take the bride away, and the Duchess of Urbino was to accompany it.

Ed altre cose che egli disse per maggiormente magnificare il fatto. Matteo Carlo to the Duke of Ferrara, Rome, September 11, 1501.

September 14th Caesar Borgia returned from Naples, where Federico, the last Aragonese king of that country, had been forced to yield to France. To his great satisfaction he found Lucretia prospective Duchess of Ferrara. On the fifteenth Ercole's envoys, Saraceni and Bellingeri, appeared. Their object was to see that the Pope fulfilled his obligations promptly. The duke was a practical man; he did not trust him. He was unwilling to send the bridal escort until he had the papal bull in his own hands. Lucretia supported the ambassador so zealously that Saraceni wrote his master that she already appeared to him to be a good Ferrarese.

Quale mi pare già essere optima Ferrarese. Despatch from Rome, September 15th.

She was present in the Vatican while Alexander carried on the negotiations. He sometimes used Latin for the purpose of displaying his linguistic attainments; but on one occasion, out of regard for Lucretia, he ordered that Italian be used, which proves that his daughter was not a perfect mistress of the classic tongue.

From this ambassador's despatches it appears that life in the Vatican was extremely agreeable. They sang, played and danced every evening. One of Alexander's greatest delights was to watch beautiful women dancing, and when Lucretia and the ladies of her court were so engaged he was careful to summon the Ferrarese ambassadors so that they might note his daughter's grace. One evening he remarked laughingly that "they might see that the duchess was not lame."

Che voleva havessimo veduto che la Duchessa non era zoppa. Saraceni to Ercole, Rome, September 16th.

The Pope never tired of passing the nights in this way, although Caesar, a strong man, was worn out by the ceaseless round of pleasure. When the latter consented to grant the ambassadors an audience, a favor which was not often bestowed even on cardinals, he received them dressed, but lying in bed, which caused Saraceni to remark in his despatch, "I feared that he was sick, for last evening he danced without intermission, which he will do again tonight at the Pope's palace, where the illustrious duchess is going to sup."

Rome, September 23d, Saraceni.

Lucretia regarded it as a relief when, a few days later, the Pope went to Civitacastellana and Nepi. September 25th the ambassadors wrote to Ferrara, "The illustrious lady continues somewhat ailing, and is greatly fatigued; she is not, however, under the care of any physician, nor does she neglect her affairs, but grants audiences as usual. We think that this indisposition merely indicates that her Majesty should take better care of herself. The rest which she will have while his Holiness is away will do her good; for whenever she is at the Pope's palace, the entire night, until two or three o'clock, is spent in dancing and at play, which fatigues her greatly."

Despatch, September 25th.

About this time occurred a disagreeable episode in connection with Giovanni Sforza, Lucretia's divorced husband, which the Pope discussed with the Ferrarese ambassadors. What they feared from him is revealed by the following despatch:

Illustrious Prince and Master: As his Holiness the Pope desires to take all proper precautions to prevent the occurrence of anything that might be unpleasant to your Excellency, to Don Alfonso, and especially to the duchess, and also to himself, he has asked us to write your Excellency and request that you see to it that Lord Giovanni of Pesaro—who, his Holiness has been informed, is in Mantua—shall not be in Ferrara at the time of the marriage festivities. For, although his divorce from the above named illustrious lady was absolutely legal and according to prescribed form, as the records of the proceedings clearly show, he himself fully consenting to it, he may, nevertheless, still harbor some resentment. If he should be in Ferrara there would be a possibility of his seeing the lady, and her Excellency would therefore be compelled to remain in concealment to escape disagreeable memories. He, therefore, requests your Excellency to prevent this possibility with your usual foresight. Thereupon his Holiness freely expressed his opinion of the Marchese of Mantua, and censured him severely because he of all the Italian princes was the only one who offered an asylum to outcasts, and especially to those who were under not only his own ban, but under that of his Most Christian Majesty. We endeavored, however, to excuse the marchese by saying that he, a high-minded man, could not close his domain to such as wished to come to him, especially when they were people of importance, and we used every argument to defend him. His Holiness, however, seemed displeased by our defense of the marchese. Your Excellency may, therefore, make such arrangements as in your wisdom seem proper. And so we, in all humility, commend ourselves to your mercy.

Rome, September 23, 1501.

To this Ercole replied in reassuring terms. Letter to his orators in Rome, September 18, 1501.

As a result of Ercole's insistence, the question of the reduction of Ferrara's yearly tribute as a fief of the Holy See from four hundred ducats to one hundred florins was brought to a vote in the consistory, September 17th. It was expected that there would be violent opposition. Alexander explained what Ercole had done for Ferrara, his founding convents and churches, and his strengthening the city, thus making it a bulwark for the States of the Church. The cardinals were induced to favor the reduction by the intervention of the Cardinal of Cosenza—one of Lucretia's creatures—and of Messer Troche, Caesar's confidant. They authorized the reduction and the Pope thanked them, especially praising the older cardinals—the younger, those of his own creation, having been more obstinate.

Despatch of Matteo Carlo to Ercole, Rome, September 18, 1501.

The same day he secured possession of the property he had wrested from the barons who had been placed under his ban August 20th. These domains, which embraced a large part of the Roman Campagna, were divided into two districts. The center of one was Nepi; that of the other Sermoneta—two cities which Lucretia, their former mistress, immediately renounced. Alexander made these duchies over to two children, Giovanni Borgia and Rodrigo. At first the Pope ascribed the paternity of the former child to his own son Caesar, but subsequently he publicly announced that he himself was its father.

It is difficult to believe in such unexampled shamelessness, but the legal documents to prove it are in existence. Both bulls are dated September 1, 1501, and are addressed to my beloved son, "the noble Giovanni de Borgia and Infante of Rome." In the former, Alexander states that Giovanni, a child of three years, was the natural son of Caesar Borgia, unmarried (which he was at the time of its birth), by a single woman. By apostolic authority he legitimated the child and bestowed upon it all the rights of a member of his family. In the second brief he refers to the proceedings in which the child had been declared to be Caesar's son, and says verbatim: "Since it is owing, not to the duke named (Caesar), but to us and to the unmarried woman mentioned that you bear this stain (of illegitimate birth), which for good reasons we did not wish to state in the preceding instrument; and in order that there may be no chance of your being caused annoyance in the future, we will see to it that that document shall never be declared null, and of our own free will, and by virtue of our authority, we confirm you, by these presents, in the full enjoyment of everything as provided in that instrument." Thereupon he renews the legitimation and announces that even if this his child, which had hitherto been declared to be Caesar's, shall in future, in any document or act be named and described as his (Caesar's), and even if he uses Caesar's arms, it shall in no way inure to the disadvantage of the child, and that all such acts shall have the same force which they would have had if the boy had been described not as Caesar's, but as his own, in the documents referring to his legitimation.

Both bulls are in the archives of Modena. The first is a copy, the second an original. The lead seal is wanting, but the red and yellow silk by which it was attached is still preserved. I first discovered the facts in a manuscript in the Barberiniana in Rome.

It is worthy of note that both these documents were executed on one and the same day, but this is explained by the fact that the canon law prevented the Pope from acknowledging his own son. Alexander, therefore, extricated himself from the difficulty by telling a falsehood in the first bull. This lie made the legitimation of the child possible, and also conferred upon it the rights of succession; and this having once been embodied in a legal document, the Pope could, without injury to the child, tell the truth.

September 1, 1501, Caesar was not in Rome. Even a man of his stamp may have blushed for his father, when he thus made him the rival of this bastard for the possession of the property. Later, after Alexander's death, the little Giovanni Borgia passed for Caesar's son; he had, moreover, been described as such by the Pope in numerous briefs.

Mandate of the Pope regarding certain taxes, dated July 21, 1502: Nobili Infanti Johanni Borgia, nostro secundum carnem nepoti; and in another brief, dated June 12, 1502, Dil filii nobilis infantis Johannis Borgia ducis Nepesini delecti filii nobilis viri Caesaris Borgia de Francia, etc. Archives of Modena.

It is not known who was the mother of this mysterious child. Burchard speaks of her merely as a "certain Roman." If Alexander, who described her as an "unmarried woman," told the truth, Giulia Farnese could not have been its mother.

It is possible, however, that the Pope's second statement likewise was untrue, and that the "Infante of Rome" was not his son, but was a natural child of Lucretia. The reader will remember that in March, 1498, the Ferrarese ambassador reported to Duke Ercole that it was rumored in Rome that the Pope's daughter had given birth to a child. This date agrees perfectly with the age of the Infante Giovanni in September, 1501. Both documents regarding his legitimation, which are now preserved in the Este archives, were originally in Lucretia's chancellery. She may have taken them with her from Rome to Ferrara, or they may have been brought to her later. Eventually we shall find the Infante at her court in Ferrara, where he was spoken of as her "brother." These facts suggest that the mysterious Giovanni Borgia was Lucretia's son—this, however, is only a hypothesis. The city of Nepi and thirty-six other estates were conferred upon the child as his dukedom.

The second domain, including the duchy of Sermoneta and twenty-eight castles, was given to little Rodrigo, Lucretia's only son by Alfonso of Aragon.

Under Lucretia's changed conditions, this child was an embarrassment to her, for she either was not allowed or did not dare to bring a child by her former husband to Ferrara. For the sake of her character let us assume that she was compelled to leave her child among strangers. The order to do so, however, does not appear to have emanated from Ferrara, for, September 28th, the ambassador Gerardi gave his master an account of a call which he made on Madonna Lucretia, in which he said, "As her son was present, I asked her—in such a way that she could not mistake my meaning—what was to be done with him; to which she replied, 'He will remain in Rome, and will have an allowance of fifteen thousand ducats.'"

Geradi to Ercole, Rome, September 28th.

The little Rodrigo was, in truth, provided for in a princely manner. He was placed under the guardianship of two cardinals—the Patriarch of Alexandria and Francesco Borgia, Archbishop of Cosenza. He received the revenues of Sermoneta, and he also owned Biselli, his unfortunate father's inheritance; for Ferdinand and Isabella of Castile authorized their ambassador in Rome, Francesco de Roxas, January 7, 1502, to confirm Rodrigo in the possession of the duchy of Biselli and the city of Quadrata. According to this act his title was Don Rodrigo Borgia of Aragon, Duke of Biselli and Sermoneta, and lord of Quadrata.

Datum in civitate Hispali, January 7, 1502. Yo el rey. Archives of Modena. In Liber Arrendamentorum Terrarum ad Illmos Dnos Rodericum Bor. de Aragonia Sermoneti, et Jo. de bor., Nepesin. Duces infantes spectantium et alearq. scripturar. status eorundem tangentium. Biselli, 1502.

外部リンク

Chapter XXI: The Eve of the Wedding

Lucretia was impatient to leave Rome, which, she remarked to the ambassador of Ferrara, seemed to her like a prison; the duke himself was no less anxious to conclude the transaction. The preparation of the new bull of investiture, however, was delayed, and the cession of Cento and Pievi could not be effected without the consent of Cardinal Giuliano della Rovere, Archbishop of Bologna, who was then living in France. Ercole, therefore, postponed despatching the bridal escort, although the approach of winter would make the journey, which was severe at any time, all the more difficult. Whenever Lucretia saw the Ferrarese ambassadors she asked them how soon the escort would come to fetch her. She herself endeavored to remove all obstacles. Although the cardinals trembled before the Pope and Caesar, they were reluctant to sign a bull which would lose Ferrara's tribute to the Church. They were bitterly opposed to allowing the descendants of Alfonso and Lucretia, without limitation, to profit by a remission of the annual payment; they would suffer this privilege to be enjoyed for three generations at most. The duke addressed urgent letters to the cardinal and to Lucretia, who finally, in October, succeeded in arranging matters, thereby winning high praise from her father-in-law. During the first half of October she and the duke kept up a lively correspondence, which shows that their mutual confidence was increasing. It was plain that Ercole was beginning to look upon the unequal match with less displeasure, as he discovered that his daughter-in-law possessed greater sense than he had supposed. Her letters to him were filled with flattery, especially one she wrote when she heard he was sick, and Ercole thanked her for having written it with her own hand, which he regarded as special proof of her affection.

Lucretia to Ercole, October 18th; Ercole to Lucretia, October 23d.

The ambassadors reported to him as follows: "When we informed the illustrious Duchess of your Excellency's illness, her Majesty displayed the greatest concern. She turned pale and stood for a moment bowed in thought. She regretted that she was not in Ferrara to take care of you herself. When the walls of the Vatican salon tumbled in, she nursed his Holiness for two weeks without resting, as the Pope would allow no one else to do anything for him."

Gerardo to Ercole, October 15, 1501.

Well might the illness of Lucretia's father-in-law frighten her. His death would have delayed, if not absolutely prevented, her marriage with Alfonso; for up to the present time she had no proof that her prospective husband's opposition had been overcome.

There are no letters written by either to the other at this time—a silence which is, to say the least, singular. Still more disturbing to Lucretia must have been the thought that her father himself might die, for his death would certainly set aside her betrothal to Alfonso. Shortly after Ercole's illness Alexander fell sick. He had caught cold and lost a tooth. To prevent exaggerated reports reaching Ferrara, he had the duke's envoy summoned, and directed him to write his master that his indisposition was insignificant. "If the duke were here," said the Pope, "I would—even if my face is tied up—invite him to go and hunt wild boars." The ambassador remarked in his despatch that the Pope, if he valued his health, had better change his habits, and not leave the palace before daybreak, and had better return before nightfall.

Ercole to Don Francesco de Roxas, October 24, 1501.

Ercole and the Pope received congratulations from all sides. Cardinals and ambassadors in their letters proclaimed Lucretia's beauty and graciousness. The Spanish envoy in Rome praised her in extravagant terms, and Ercole thanked him for his testimony regarding the virtues of his daughter-in-law.

Gerardo Saraceni to Ercole, Rome, October 26, 1501.

Even the King of France displayed the liveliest pleasure at the event, which, he now discovered, would redound greatly to Ferrara's advantage. The Pope, beaming with joy, read the congratulations of the monarch and his consort to the consistory. Louis XII even condescended to address a letter to Madonna Lucretia, at the end of which were two words in his own hand. Alexander was so delighted thereby that he sent a copy of it to Ferrara. The court of Maximilian was the only one from which no congratulations were received. The emperor exhibited such displeasure that Ercole was worried, as the following letter to his plenipotentiaries in Rome shows:

The Duke of Ferrara, etc.

Our Well-Loved: We have given his Holiness, our Lord, no further information regarding the attitude of the illustrious Emperor of the Romans towards him since Messer Michele Remolines departed from here, for we had nothing definite to communicate. We have, however, been told by a trustworthy person with whom the king conversed, that his Majesty was greatly displeased, and that he criticised his Holiness in unmeasured terms on account of the alliance which we have concluded with him, as he also did in letters addressed to us before the betrothal, in which he advised us not to enter into it, as you will learn from the copies of his letters which we send you with this. They were shown and read to his Holiness's ambassador here. Although, so far as we ourselves are concerned, we did not attach much importance to his Majesty's attitude, as we followed the dictates of reason, and are daily becoming more convinced that it will prove advantageous for us; it nevertheless appears

proper, in view of our relations with his Holiness, that he should be informed of our position.

You will, therefore, tell him everything, and also let him see the copies, if you think best, but you must say to him in our name that he is not to ascribe their authorship to us, and that we have not sent you these copies because of any special importance that we attached to them.

Ferrara, October 3, 1501.

The duke now allowed nothing to shake his resolution. Early in October he selected the escort whose departure from Ferrara, he frankly stated, would depend upon the progress of his negotiations with the Pope. The constitution of the bridal trains, both Roman and Ferrarese, was an important question, and is referred to in one of Gerardo's despatches.

Illustrious Sir, etc.: To-day at six o'clock Hector and I were alone with the Pope, having your letters of the twenty-sixth ultimo and of the first of the present month, and also a list of those who are to compose the escort. His Holiness was greatly pleased, the various persons being people of wealth and standing, as he could readily see, the rank and position of each being clearly indicated. I have learned from the best of sources that your Excellency has exceeded all the Pope's expectations. After we had conversed a while with his Holiness, the illustrious Duke of Romagna and Cardinal Orsini were summoned. There were also present Monsignor Elna, Monsignor Troche, and Messer Adriano. The Pope had the list read a second time, and again it was praised, especially by the duke, who said he was acquainted with several of the persons named. He kept the list, thanking me warmly when I gave it to him again, for he had returned it to me.

We endeavored to get the list of those who are to come with the illustrious Duchess, but it has not yet been prepared. His Holiness said that there would not be many women among the number, as the ladies of Rome were not skilful horsewomen.

Per essere queste romane salvatiche et male apte a cavallo.

Hitherto the Duchess has had five or six young ladies at her court—four very young girls and three married women—who will remain with her Majesty. She has, however, been advised not to bring them, as many of the great ladies in Ferrara will offer her their services. She has also a certain Madonna Girolama, Cardinal Borgia's sister, who is married to one of the Orsini. She and three of her women will accompany her. These are the only ladies of honor she has hitherto had. I have heard that she will endeavor to find others in Naples, but it is believed that she will be able to secure only a few, and that these will merely accompany her. The Duchess of Urbino has announced that she expects to come with a mounted escort of fifty persons. So far as the men are concerned, his Holiness said that there would not be many, as there were no Roman noblemen except the Orsini, and they generally were away from the city. Still, he hoped to be able to find sufficient, provided the Duke of Romagna did not take the field, there being a large number of nobles among his followers. His Holiness said that he had plenty of priests and scholars to send, but not such persons as were fit for a mission of this sort. However, the retinue furnished by your Majesty will serve for both, especially as—according to his Holiness—it is better for the more numerous escort to be sent by the groom, and for the bride to come accompanied by a smaller number. Still I do not think her suite will number less than two hundred persons. The Pope is in doubt what route her Majesty will travel. He thinks

she ought to go by way of Bologna, and he says that the Florentines likewise have invited her. Although his Holiness has reached no decision, the Duchess has informed us that she would journey through the Marches, and the Pope has just concluded that she might do so. Perhaps he desires her to pass through the estates of the Duke of Romagna on her way to Bologna.

Regarding your Majesty's wish that a cardinal accompany the Duchess, his Holiness said that it did not seem proper to him for a cardinal to leave Rome with her; but that he had written the Cardinal of Salerno, the Legate in the Marches, to go to the seat of the Duke in Romagna and wait there, and accompany the Duchess to Ferrara to read mass at the wedding. He thought that the cardinal would do this, unless prevented by sickness, in which case his Holiness would provide another.

When the Pope discovered, during this conversation, that we had so far been unable to secure an audience with the illustrious Duke, he showed great annoyance, declaring it was a mistake which could only injure his Majesty, and he added that the ambassadors of Rimini had been here two months without succeeding in speaking with him, as he was in the habit of turning day into night and night into day. He severely criticized his son's mode of living. On the other hand, he commended the illustrious Duchess, saying that she was always gracious, and granted audiences readily, and that whenever there was need she knew how to cajole. He lauded her highly, and stated that she had ruled Spoleto to the satisfaction of everybody, and he also said that her Majesty always knew how to carry her point-even with himself, the Pope. I think that his Holiness spoke in this way more for the purpose of saying good of her (which according to my opinion she deserved) than to avoid saying anything ill, even if there were occasion for it. Your Majesty's Ever devoted.

Rome, October 6th.

The Pope seldom allowed an opportunity to pass for praising his daughter's beauty and graciousness. He frequently compared her with the most famous women of Italy—the Marchioness of Mantua and the Duchess of Urbino. One day, while conversing with the ambassadors of Ferrara, he mentioned her age, saying that in October (1502) she would complete her twenty-second year, while Caesar would be twenty-six the same month.

Gerardo to Ercole, October 26, 1501.

The Pope was greatly pleased with the members of the bridal escort, for they all were either princes of the house of Este or prominent persons of Ferrara. He also approved the selection of Annibale Bentivoglio, son of the Lord of Bologna, and said laughingly to the Ferrarese ambassadors that, even if their master had chosen Turks to come to Rome for the bride, they would have been welcome.

The Florentines, owing to their fear of Caesar, sent ambassadors to Lucretia to ask her to come by way of their city when she went to Ferrara; the Pope, however, was determined that she should make the journey through Romagna. According to an oppressive custom of the day, the people through whose country persons of quality traveled were required to provide for them, and, in order not to tax Romagna too heavily, it was decided that the Ferrarese escort should come to Rome by way of Tuscany. The Republic of Florence firmly refused to entertain the escort all the time it was in its territory, although it was willing to care for it while in the city or to make a handsome present.

The orator Manfredo Manfredi to Ercole, Florence, November 22 and 24, 1501.

In the meantime preparations were under way in Ferrara for the wedding festivities. The Duke invited all the princes who were friendly to him to be present. He had even thought of the oration which was to be delivered in Ferrara when Lucretia was given to her husband. During the Renaissance these orations were regarded as of the greatest importance, and he was anxious to secure a speaker who could be depended upon to deliver a masterpiece. Ercole had instructed his ambassadors in Rome to send him particulars regarding the house of Borgia for the orator to use in preparing his speech.

The duke to his ambassadors in Rome, October 7, 1501.

The ambassadors scrupulously carried out their instructions, and wrote their sovereign as follows:

Illustrious Prince and Master: We have spared no efforts to learn everything possible regarding the illustrious house of Borgia, as your Excellency commanded. We made a thorough investigation, and members of our suite here in Rome, not only the scholars but also those who we knew were loyal to you, did the same. Although we finally succeeded in ascertaining that the house is one of the noblest and most ancient in Spain, we did not discover that its founders ever did anything very remarkable, perhaps because life in that country is quiet and uneventful—your Excellency knows that such is the case in Spain, especially in Valencia.

Whatever there is worthy of note dates from the time of Calixtus, and, in fact, the deeds of Calixtus himself are those most worthy of comment; Platina, however, has given an account of his life, which, moreover, is well known to everybody. Whoever is to deliver the oration has ample material, therefore, from which to choose. We, illustrious Sir, have been able to learn nothing more regarding this house than what you already know, and this concerns only the members of the family who have been Popes, and is derived chiefly from the audience speeches. In case we succeed in finding out anything more, we shall inform your Excellency, to whom we commend ourselves in all humility.

Rome, October 18, 1501.

When the descendant of the ancient house of Este read this terse despatch he must have smiled; its candor was so undiplomatic that it bordered on irony. The doughty ambassadors, however, apparently did not go to the right sources, for if they had applied to the courtiers who were intimate with the Borgia—for example, the Porcaro—they would have obtained a genealogical tree showing a descent from the old kings of Aragon, if not from Hercules himself.

In the meantime the impatience of the Pope and Lucretia was steadily increasing, for the departure of the bridal escort was delayed, and the enemies of the Borgia were already beginning to make merry. The duke declared that he could not think of sending for Donna Lucretia until the bull of investiture was in his hands. He complained at the Pope's delay in fulfilling his promises. He also demanded that the part of the marriage portion which was to be paid in coin through banking houses in Venice, Bologna, and other cities be handed over on the bridal escort's entry into Rome, and threatened in case it was not paid in full to have his people return to Ferrara without the bride.

Ercole to Gerardo Saraceni, November 24, 1501. Other letters of like import were written by the duke to his plenipotentiaries.

As it was impossible for him to bring about the immediate cession of Cento and Pievi, he asked from the Pope as a pledge that either the bishopric of Bologna be given his son Ippolito, or that his Holiness furnish a bond. He also demanded certain benefices for his natural son Don Giulio, and for his ambassador Gianluca Pozzi. Lucretia succeeded in securing the bishopric of Reggio for the latter and also a house in Rome for the Ferrarese envoy.

Another important question was the dowry of jewels which Lucretia was to receive. During the Renaissance the passion for jewels amounted to a mania. Ercole sent word to his daughter-in-law that she must not dispose of her jewels, but must bring them with her; he also said that he would send her a handsome ornament by the bridal escort, gallantly adding that, as she herself was a precious jewel, she deserved the most beautiful gems—even more magnificent ones than he and his own consort had possessed; it is true he was not so wealthy as the Duke of Savoy, but, nevertheless, he was in a position to send her jewels no less beautiful than those given her by the duke.

Ercole to Gerardo Saraceni in Rome, October 11, 1501.

The relations between Ercole and his daughter-in-law were as friendly as could be desired, for Lucretia exerted herself to secure the Pope's consent to his demands. His Holiness, however, was greatly annoyed by the duke's conduct; he sent urgent requests to him to despatch the escort to Rome, and assured him that the two castles in Romagna would be delivered over to him before Lucretia reached Ferrara, but in case she did arrive there first that everything she asked would be granted—his love for her was such that he even thought of paying her a visit in Ferrara in the spring.

Despatch of the Ferrarese ambassadors to Ercole, Rome, October 31, 1501.

The Pope suspected, however, that the delay in sending the bridal escort was due to the machinations of Maximilian. Even as late as November the emperor had despatched his secretary, Agostino Semenza, to the duke to warn him not to send the escort to Rome, adding that he would show his gratitude to Ercole. November 22d the duke wrote the imperial plenipotentiary a letter in which he stated that he had immediately sent a courier to his ambassador in Rome; it would soon be winter, and the time would therefore be unfavorable for bringing Lucretia; if the Pope was willing, he would postpone the wedding, but he would not break off with him entirely. His Majesty should remember that if he did this, the Pope would become his bitterest enemy, and would persecute him, and might even make war on him. It was, he stated, for the express purpose of avoiding this that he had consented to enter into an alliance with his Holiness. He, therefore, hoped that his Majesty would not expose him to this danger, but that, with his usual justice, he would appreciate his excuses.

Il quale mal effecto volendo nui fugire, seamo condescesi a contrahere la affinita cum soa Santità. Responsum illmi Dni ducis Ferrarie D. Augustino Semetie Ces Mtis secretario. Ferrara, November 22, 1501.

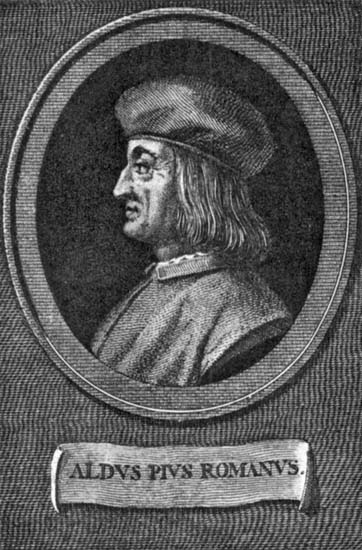

ERCOLE D'ESTE, DUKE OF FERRARA.

At the same time he instructed his ambassadors in Rome to inform the Pope of the emperor's threats, and to say to him that he was ready to fulfil his own obligations and also to urge his Holiness to have the bulls prepared at once, as further delay was dangerous.

Alexander thereupon fell into a rage; he overwhelmed the ambassadors with reproaches, and called the duke a "tradesman." On December 1st Ercole announced to the emperor's messenger that he was unable longer to delay sending the bridal escort, for, if he did, it would mean a rupture with the Pope. The same day he wrote to his ambassadors in Rome and complained of the use of the epithet "tradesman," which the Pope had applied to him.

Che il procedere del Duca era un procedere da mercatante. Ercole to Gerardo Saraceni, December 1, 1501.

He, however, reassured his Holiness by informing him that he had decided to despatch the bridal escort from Ferrara the ninth or tenth of December.

Ercole to Alexander VI, December 1, 1501.

GUICCIARDINI

外部リンク

Chapter XXII: Arrival and Return of the Bridal Escort

In the meantime Lucretia's trousseau was being prepared with an expense worthy of a king's daughter. On December 13, 1501, the agent in Rome of the Marchese Gonzaga wrote his master as follows: "The portion will consist of three hundred thousand ducats, not counting the presents which Madonna will receive from time to time. First a hundred thousand ducats are to be paid in money in instalments in Ferrara. Then there will be silverware to the value of three thousand ducats; jewels, fine linen, costly trappings for horses and mules, together worth another hundred thousand. In her wardrobe she has a trimmed dress worth more than fifteen thousand ducats, and two hundred costly shifts, some of which are worth a hundred ducats apiece; the sleeves alone of some of them cost thirty ducats each, being trimmed with gold fringe." Another person reported to the Marchesa Isabella that Lucretia had one dress worth twenty thousand ducats, and a hat valued at ten thousand. "It is said," so the Mantuan agent writes, "that more gold has been prepared and sold here in Naples in six months than has been used heretofore in two years. She brings her husband another hundred thousand ducats, the value of the castles (Cento and Pieve), and will also secure the remission of Ferrara's tribute. The number of horses and persons the Pope will place at his daughter's disposal will amount to a thousand. There will be two hundred carriages—among them some of French make, if there is time—and with these will come the escort which is to take her."

Despatch of Giovanni Lucido, in the archives of Mantua.

The duke finally concluded to send the bridal escort, although the bulls were not ready for him. As he was anxious to make the marriage of his son with Lucretia an event of the greatest magnificence, he sent a cavalcade of more than fifteen hundred persons for her. At their head were Cardinal Ippolito and five other members of the ducal house; his brothers, Don Ferrante and Don Sigismondo; also Niccolò Maria d'Este, Bishop of Adria; Meliaduse d'Este, Bishop of Comacchio; and Don Ercole, a nephew of the duke. In the escort were numerous prominent friends and kinsmen or vassals of the house of Ferrara, lords of Correggio and Mirandola; the Counts Rangone of Modena; one of the Pio of Carpi; the Counts Bevilacqua, Roverella, Sagrato, Strozzi of Ferrara, Annibale Bentivoglio of Bologna, and many others.

These gentlemen, magnificently clad, and with heavy gold chains about their necks, mounted on beautiful horses, left Ferrara December 9th, with thirteen trumpeters and eight fifes at their head; and thus this wedding cavalcade, led by a worldly cardinal, rode noisily forth upon their journey. In our time such an aggregation might easily be mistaken for a troop of trick riders. Nowhere did this brave company of knights pay their reckoning; in the domain of Ferrara they lived on the duke; in other words, at the expense of his subjects. In the lands of other lords they did the same, and in the territory of the Church the cities they visited were required to provide for them.

In spite of the luxury of the Renaissance, traveling was at that time very disagreeable; everywhere in Europe it was as difficult then as it is now in the Orient. Great lords and ladies, who to-day flit across the country in comfortable railway carriages, traveled in the sixteenth century, even in the most civilized states of Europe, mounted on horses or mules, or slowly in sedan-chairs, exposed to all the inclemencies of wind and weather, and unpaved roads. The cavalcade was thirteen days on the way from Ferrara to Rome—a journey which can now be made in a few hours.

Finally, on December 22d, it reached Monterosi, a wretched castle fifteen miles from Rome. All were in a deplorable condition, wet to the skin by winter rains, and covered with mud; and men and horses completely tired out. From this place the cardinal sent a messenger with a herald to Rome to receive the Pope's commands. Answer was brought that they were to enter by the Porta del Popolo.

The entrance of the Ferrarese into Rome was the most theatrical event that occurred during the reign of Alexander VI. Processions were the favorite spectacles of the Middle Ages; State, Church, and society displayed their wealth and power in magnificent cavalcades. The horse was symbolic of the world's strength and magnificence, but with the disappearance of knighthood it lost its place in the history of civilization. How the love of form and color of the people of Italy—the home of processions—has changed was shown in Rome, July 2, 1871, when Victor Emmanuel entered his new capital. Had this episode—one of the weightiest in the whole history of Italy—occurred during the Renaissance, it would have been made the occasion of a magnificent triumph. The entrance into Rome of the first king of united Italy was made, however, in a few dust-covered carriages, which conveyed the monarch and his court from the railway station to their lodgings; yet in this bourgeois simplicity there was really more moral greatness than in any of the triumphs of the Caesars. That the love of parades which existed in the Renaissance has died out is, perhaps, to be regretted, for occasions still arise when they are necessary.

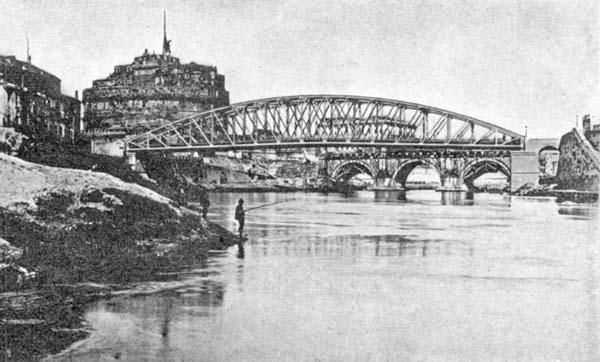

CASTLE OF S. ANGELO, ROME.

Alexander's prestige would certainly have suffered if, on the occasion of a family function of such importance, he had failed to offer the people as evidence of his power a brilliant spectacle of some sort. The very fact that Adrian VI did not understand and appreciate this requirement of the Renaissance made him the butt of the Romans.

At ten o'clock on the morning of December 23d the Ferrarese reached the Ponte Molle, where breakfast was served in a nearby villa. The appearance of this neighborhood must at that time have been different from what it is to-day. There were casinos and wine houses on the slopes of Monte Mario—whose summit was occupied even at that time by a villa belonging to the Mellini—and on the hills beyond the Flaminian Way. Nicholas V had restored the bridge over the Tiber, and also begun a tower nearby, which Calixtus III completed. Between the Ponte Molle and the Porta del Popolo there was then,—just as there is now,—a wretched suburb.

At the bridge crossing the Tiber they found a wedding escort composed of the senators of Rome, the governor of the city, and the captain of police, accompanied by two thousand men, some on foot and some mounted. Half a bowshot from the gate the cavalcade met Caesar's suite. First came six pages, then a hundred mounted noblemen, followed by two hundred Swiss clothed in black and yellow velvet with the arms of the Pope, birettas on their heads, and bearing halberds. Behind them rode the Duke of Romagna with the ambassador of France at his side, who wore a French costume and a golden sash. After greeting each other mid the blare of trumpets, the gentlemen dismounted from their horses. Caesar embraced Cardinal Ippolito and rode at his side as far as the city gate. If Valentino's following numbered four thousand and the city officials two thousand more, it is difficult to conceive, taking the spectators also into account, how so large a number of people could congregate before the Porta del Popolo. The rows of houses which now extend from this gate could not have been in existence then, and the space occupied by the Villa Borghese must have been vacant. At the gate the cavalcade was met by nineteen cardinals, each accompanied by two hundred persons. The reception here, owing to the oration, required over two hours, consequently it was evening when it was over.

Finally, to the din of trumpets, fifes, and horns, the cavalcade set out over the Corso, across the Campo di Fiore, for the Vatican, where it was saluted from Castle S. Angelo. Alexander stood at a window of the palace to see the procession which marked the fulfilment of the dearest wish of his house. His chamberlain met the Ferrarese at the steps of the palace and conducted them to his Holiness, who, accompanied by twelve cardinals, advanced to meet them. They kissed his feet, and he raised them up and embraced them. A few moments were spent in animated conversation, after which Caesar led the princes to his sister. Leaning on the arm of an elderly cavalier dressed in black velvet, with a golden chain about his neck, Lucretia went as far as the entrance of her palace to greet them. According to the prearranged ceremonial she did not kiss her brothers-in-law, but merely bowed to them, following the French custom. She wore a dress of some white material embroidered in gold, over which there was a garment of dark brown velvet trimmed with sable. The sleeves were of white and gold brocade, tight, and barred in the Spanish fashion. Her head-dress was of a green gauze, with a fine gold band and two rows of pearls. About her neck was a heavy chain of pearls with a ruby pendant. Refreshments were served, and Lucretia distributed small gifts—the work of Roman jewelers—among those present. The princes departed highly pleased with their reception. "This much I know," wrote El Prete, "that the eyes of Cardinal Ippolito sparkled, as much as to say, She is an enchanting and exceedingly gracious lady."

The cardinal likewise wrote the same evening to his sister Isabella of Mantua to satisfy her curiosity regarding Lucretia's costume. Dress was then an important matter in the eyes of a court; in fact there never was a time when women's costumes were richer and more carefully studied than they were during the Renaissance. The Marchioness had sent an agent to Rome apparently for the sole purpose of giving her an account of the bridal festivities, and she had directed him to pay special attention to the dresses. El Prete carried out his instructions as conscientiously as a reporter for a daily paper would now do.

The report of this agent, who signs himself El Prete, is preserved in the archives of Mantua.

From his description an artist could paint a good portrait of the bride.

The same evening the Ferrarese ambassadors paid their official visit to Donna Lucretia, and they promptly wrote the duke regarding the impression his daughter-in-law had made upon them.

Illustrious Master: To-day after supper Don Gerardo Saraceni and I betook ourselves to the illustrious Madonna Lucretia, to pay our respects in the name of your Excellency and his Majesty Don Alfonso. We had a long conversation regarding various matters. She is a most intelligent and lovely, and also exceedingly gracious lady. Your Excellency and the illustrious Don Alfonso—so we were led to conclude—will be highly pleased with her. Besides being extremely graceful in every way, she is modest, lovable, and decorous. Moreover, she is a devout and God-fearing Christian. To-morrow she is going to confession, and during Christmas week she will receive the communion. She is very beautiful, but her charm of manner is still more striking. In short, her character is such that it is impossible to suspect anything "sinister" of her; but, on the contrary, we look for only the best. It seems to be our duty to tell you the exact truth in this letter. I commend myself to your Highness's merciful benevolence. Rome, December 23, 1501, the sixth hour of the night.

Your Excellency's servant,

Johannes Lucas.

Pozzi's letter shows how anxious were the duke and his son, even up to the last. It must have been a humiliation for both of them to have to confide their suspicions to their ambassador in Rome, and to ask him to find out what he could regarding the character of a lady who was to be the future Duchess of Ferrara. The very phrase in Pozzi's letter that there was nothing "sinister" to be suspected of Lucretia shows how black were the rumors that circulated regarding her. His testimony, therefore, is all the more valuable, and it is one of the most important documents for forming a judgment of Lucretia's character. Had she been afforded a chance to read it, her mortification would, no doubt, have outweighed her satisfaction.

The Farrarese agent, Bartolomeo Bresciani, who had been sent to Rome on matters connected with the Church, is no less complimentary. He says, la Excell. V. remagnera molto ben satisfacto da questa Illma Madona per essere dotada de tanti costumi et buntade. (To the duke, October 30, 1501.) He informed him also that Lucretia often conversed with a saintly person who had been secluded in the Vatican for eight years.

The Ferrarese princes took up their abode in the Vatican; other gentlemen occupied the Belvedere, while the majority were provided for by the citizens, who were compelled to entertain them. At that time the popes handled their private matters just as if they were affairs of state, and met expenses by taxing the court officials, who, in spite of this, made a good living, and even grew rich by the Pope's mercy. The merchants likewise were required to bear a part of the expense of these ecclesiastical functions. Many of the officials grumbled over entertaining the Ferrarese, and provided for them so badly that the Pope was compelled to interfere.

Despatch of Gianluca Pozzi to Ercole, Rome, December 25, 1501.

During the Christmas festivities the Pope read mass in S. Peter's. The princes were present, and the duke's ambassador described Alexander's magnificent and also "saintly" bearing in terms more fitting to depict the appearance of an accomplished actor.

Pozzi to Ercole, Rome, December 25, 1501.

The Pope now gave orders for the carnival to begin, and there were daily banquets and festivities in the Vatican.

El Prete has left a naive account of an evening's entertainment in Lucretia's palace, in which he gives us a vivid picture of the customs of the day. "The illustrious Madonna," so wrote the reporter, "appears in public but little, because she is busy preparing for her departure. Sunday evening, S. Stephen's Day, December 26th, I went unexpectedly to her residence. Her Majesty was in her chamber, seated by the bed. In a corner of the room were about twenty Roman women dressed a la romanesca, 'wearing certain cloths on their heads'; the ladies of her court, to the number of ten, were also present. A nobleman from Valencia and a lady of the court, Niccola, led the dance. They were followed by Don Ferrante and Madonna, who danced with extreme grace and animation. She wore a camorra of black velvet with gold borders and black sleeves; the cuffs were tight; the sleeves were slashed at the shoulders; her breast was covered up to the neck with a veil made of gold thread. About her neck she wore a string of pearls, and on her head a green net and a chain of rubies. She had an overskirt of black velvet trimmed with fur, colored, and very beautiful. The trousseaux of her ladies-in-waiting are not yet ready. Two or three of the women are pretty; one, Catalina, a native of Valencia, dances well, and another, Angela, is charming. Without telling her, I picked her out as my favorite. Yesterday evening (28th) the cardinal, the duke, and Don Ferrante walked about the city masked, and afterwards we went to the duchess's house, where there was dancing. Everywhere in Rome, from morning till night, one sees nothing but courtesans wearing masks, for after the clock strikes the twenty-fourth hour they are not permitted to show themselves abroad."

Although the marriage had been performed in Ferrara by proxy, Alexander wished the service to be said again in Rome. To prevent repetition, the ceremony in Ferrara had been performed only vis volo, the exchange of rings having been deferred.

On the evening of December 30th, the Ferrarese escorted Madonna Lucretia to the Vatican. When Alfonso's bride left her palace she was accompanied by her entire court and fifty maids of honor. She was dressed in gold brocade and crimson velvet trimmed with ermine; the sleeves of her gown reached to the floor; her train was borne by some of her ladies; her golden hair was confined by a black ribbon, and about her neck she wore a string of pearls with a pendant consisting of an emerald, a ruby, and a large pearl.

Don Ferrante and Sigismondo led her by the hands; when the train set forth a body of musicians stationed on the steps of S. Peter's began to play. The Pope, on the throne in the Sala Paolina, surrounded by thirteen cardinals and his son Caesar, awaited her. Among the foreign representatives present were the ambassadors of France, Spain, and Venice; the German envoy was absent. The ceremony began with the reading of the mandate of the Duke of Ferrara, after which the Bishop of Adria delivered the wedding sermon, which the Pope, however, commanded to be cut short.

Fu necessario che la abreviasse, Gianluca and Gerardo to Ercole, Rome, December 30, 1501.

A table was placed before him, and by it stood Don Ferrante—as his brother's representative—and Donna Lucretia. Ferrante addressed the formal question to her, and on her answering in the affirmative, he placed the ring on her finger with the following words: "This ring, illustrious Donna Lucretia, the noble Don Alfonso sends thee of his own free will, and in his name I give it thee"; whereupon she replied, "And I, of my own free will, thus accept it."

The performance of the ceremony was attested by a notary. Then followed the presentation of the jewels to Lucretia by Cardinal Ippolito. The duke, who sent her a costly present worth no less than seventy thousand ducats, attached special weight to the manner in which it was to be given her. On December 21st he wrote his son that in presenting the jewels he should use certain words which his ambassador Pozzi would give him, and he was told that this was done as a precautionary measure, so that, in case Donna Lucretia should prove untrue to Alfonso, the jewels would not be lost.

E ciò nello scopo, che se mancasse essa Duchessa verso lo Illmo Don Alfonso non fosse più obbligato di quanto voleva esserlo circa dette gioje. Ercole to Cardinal Ippolito, December 21, 1501. There is a letter of the same date regarding the subject, written by Ercole to Gianluca Pozzi.

Until the very last, the duke handled the Borgias with the misgivings of a man who feared he might be cheated. On December 30th Pozzi wrote him: "There is a document regarding this marriage which simply states that Donna Lucretia will be given, for a present, the bridal ring, but nothing is said of any other gift. Your Excellency's intention, therefore, was carried out exactly. There was no mention of any present, and your Excellency need have no anxiety."

Ippolito performed his part so gracefully that the Pope told him he had heightened the beauty of the present. The jewels were in a small box which the cardinal first placed before the Pope and then opened. One of the keepers of the jewels from Ferrara helped him to display the gems to the best advantage. The Pope took the box in his own hand and showed it to his daughter. There were chains, rings, earrings, and precious stones beautifully set. Especially magnificent was a string of pearls—Lucretia's favorite gem. Ippolito also presented his sister-in-law with his gifts, among which were four beautifully chased crosses. The cardinals sent similar presents.

After this the guests went to the windows of the salon to watch the games in the Piazza of S. Peter; these consisted of races and a mimic battle for a ship. Eight noblemen defended the vessel against an equal number of opponents. They fought with sharp weapons, and five people were wounded.

This over, the company repaired to the Chamber of the Parrots, where the Pope took his position upon the throne, with the cardinals on his left, and Ippolito, Donna Lucretia, and Caesar on his right. El Prete says: "Alexander asked Caesar to lead the dance with Donna Lucretia, which he did very gracefully. His Holiness was in continual laughter. The ladies of the court danced in couples, and extremely well. The dance, which lasted more than an hour, was followed by the comedies. The first was not finished, as it was too long; the second, which was in Latin verse, and in which a shepherd and several children appeared, was very beautiful, but I have forgotten what it represented. When the comedies were finished all departed except his Holiness, the bride, and her brother-in-law. In the evening the Pope gave the wedding banquet, but of this I am unable to send any account, as it was a family affair."

The festivities continued for days, and all Rome resounded with the noise of the carnival. During the closing days of the year Cardinal Sanseverino and Caesar presented some plays. The one given by Caesar was an eclogue, with rustic scenery, in which the shepherd sang the praises of the young pair, and of Duke Ercole, and the Pope as Ferrara's protector.

Pozzi to Ercole, January 1, 1502. Archives of Modena.

The first day of the new year (1502) was celebrated with great pomp. The various quarters of Rome organized a parade in which were thirteen floats led by the gonfalonier of the city and the magistrates, which passed from the Piazza Navona to the Vatican, accompanied by the strains of music. The first car represented the triumph of Hercules, another Julius Caesar, and others various Roman heroes. They stopped before the Vatican to enable the Pope and his guests to admire the spectacle from the windows. Poems in honor of the young couple were declaimed, and four hours were thus passed.

Then followed comedies in the Chamber of the Parrots. Subsequently a moresca or ballet was performed in the "sala of the Pope," whose walls were decorated with beautiful tapestries which had been executed by order of Innocent VIII. Here was erected a low stage decorated with foliage and illuminated by torches. The lookers-on took their places on benches and on the floor, as they preferred. After a short eclogue, a jongleur dressed as a woman danced the moresca to the accompaniment of tamborines, and Caesar also took part in it, and was recognized in spite of his disguise. Trumpets announced a second performance. A tree appeared upon whose top was a Genius who recited verses; these over, he dropped down the ends of nine silk ribbons which were taken by nine maskers who danced a ballet about the tree. This moresca was loudly applauded. In conclusion the Pope asked his daughter to dance, which she did with one of her women, a native of Valencia, and they were followed by all the men and women who had taken part in the ballet.

El Prete to Isabella, Rome, January 2, 1502.

Comedies and moresche were in great favor on festal occasions. The poets of Rome, the Porcaro, the Mellini, Inghirami, and Evangelista Maddaleni, probably composed these pieces, and they may also have taken part in them, for it was many years since Rome had been given such a brilliant opportunity to show her progress in histrionics. Lucretia was showered with sonnets and epithalamia. It is strange that not one of these has been preserved, and also that not a single Roman poet of the day is mentioned as the author of any of these comedies. On January 2d a bull fight was given in the Piazza of S. Peter's. The Spanish bull fight was introduced into Italy in the fourteenth century, but not until the fifteenth had it become general. The Aragonese brought it to Naples, and the Borgias to Rome. Hitherto the only thing of the sort which had been seen was the bull-baiting in the Piazza Navona or on the Testaccio. Caesar was fond of displaying his agility and strength in this barbarous sport. During the jubilee year he excited the wonder of all Rome by decapitating a bull with a single stroke in one of these contests. On January 2d he and nine other Spaniards, who probably were professional matadors, entered the enclosure with two loose bulls, where he mounted his horse and with his lance attacked the more ferocious one single-handed; then he dismounted, and with the other Spaniards continued to goad the animals. After this heroic performance the duke left the arena to the matadors. Ten bulls and one buffalo were slaughtered.

In the evening the Menæchmi of Plautus and other pieces were produced in which was celebrated the majesty of Caesar and Ercole. The Ferrarese ambassador sent his master an account of these performances which is a valuable picture of the day.

This evening the Menæchmi was recited in the Pope's room, and the Slave, the Parasite, the Pandor, and the wife of Menæchmus performed their parts well. The Menæchmi themselves, however, played badly. They had no masks, and there was no scenery, for the room was too small. In the scene where Menæchmus, seized by command of his father-in-law, who thinks he is mad, exclaims that he is being subjected to force, he added: "This passes understanding; for Caesar is mighty, Zeus merciful, and Hercules kind."

Before the performance of this comedy the following play was given: first appeared a boy in woman's clothes who represented Virtue, and another in the character of Fortune. They began to banter each other as to which was the mightier, whereupon Fame suddenly appeared, standing on a globe which rested on a float, upon which were the words, "Gloria Domus Borgiæ." Fame, who also called himself Light, awarded Virtue the prize over Fortune, saying that Caesar and Ercole by Virtue had overcome Fortune; thereupon he described a number of the heroic deeds performed by the illustrious Duke of Romagna. Hercules with the lion's skin and club appeared, and Juno sent Fortune to attack him. Hercules, however, overcame Fortune, seized her and chained her; whereupon Juno begged him to free her, and he, gracious and generous, consented to grant Juno's request on the condition that she would never do anything which might injure the house of Ercole or that of Caesar Borgia. To this she agreed, and, in addition, she promised to bless the union of the two houses.

Then Roma entered upon another float. She complained that Alexander, who occupied Jupiter's place, had been unjust to her in permitting the illustrious Donna Lucretia to go away; she praised the duchess highly, and said that she was the refuge of all Rome. Then came a personification of Ferrara—but not on a float—and said that Lucretia was not going to take up her abode in an unworthy city, and that Rome would not lose her. Mercury followed, having been sent by the gods to reconcile Rome and Ferrara, as it was in accordance with their wish that Donna Lucretia was going to the latter city. Then he invited Ferrara to take a seat by his side in the place of honor on the float.

All this was accompanied by descriptions in polished hexameters, which celebrated the alliance of Caesar and Ercole, and predicted that together they would overthrow all the latter's enemies. If this prophecy is realized, the marriage will result greatly to our advantage. So we commend ourselves to your Excellency's mercy.

Your Highness's servants,

Johann Lucas and Gerardus Saracenus.

January 2, 1502.

Finally the date set for Lucretia to leave—January 6th—arrived. The Pope was determined that her departure should be attended by a magnificent display; she should traverse Italy like a queen. A cardinal was to accompany her as legate, Francesco Borgia, Archbishop of Cosenza, having been chosen for this purpose. To Lucretia he owed his cardinalate, and he was a most devoted retainer; "an elderly man, a worthy person of the house of Borgia," so Pozzi wrote to Ferrara. Madonna was also accompanied by the bishops of Carniola, Venosa, and Orte.

Alexander endeavored to persuade many of the nobles of Rome, men and women, to accompany Lucretia, and he succeeded in inducing a large number to do so. The city of Rome appointed four special envoys, who were to remain in Ferrara as long as the festivities lasted—Stefano del Bufalo, Antonio Paoluzzo, Giacomo Frangipane, and Domenico Massimi. The Roman nobility selected for the same purpose Francesco Colonna of Palestrina and Giuliano, Count of Anguillara. There were also Ranuccio Farnese of Matelica and Don Giulio Raimondo Borgia, the Pope's nephew, and captain of the papal watch, together with eight other gentlemen belonging to the lesser nobility of Rome.

Caesar equipped at his own expense an escort of two hundred cavaliers, with musicians and buffoons to entertain his sister on the way. This cavalcade, which was composed of Spaniards, Frenchmen, Romans, and Italians from various provinces, was joined later by two famous men—Ivo d'Allegre and Don Ugo Moncada. Among the Romans were the Chevaliers Orsini; Piero Santa Croce; Giangiorgio Cesarini, a brother of Cardinal Giuliano; and other gentlemen, members of the Alberini, Sanguigni, Crescenzi, and Mancini families.

Lucretia herself had a retinue of a hundred and eighty people. In the list—which is still preserved—are the names of many of her maids of honor; her first lady-in-waiting was Angela Borgia, una damigella elegantisima, as one of the chroniclers of Ferrara describes her, who is said to have been a very beautiful woman, and who was the subject of some verses by the Roman poet Diomede Guidalotto. She was also accompanied by her sister Donna Girolama, consort of the youthful Don Fabio Orsini. Madonna Adriana Orsini, another woman named Adriana, the wife of Don Francesco Colonna, and another lady of the house of Orsini, whose name is not given, also accompanied Lucretia. It is not likely, however, that the last was Giulia Farnese.

A number of vehicles which the Pope had ordered built in Rome and a hundred and fifty mules bore Lucretia's trousseau. Some of this baggage was sent on ahead. The duchess took everything that the Pope permitted her to remove. He refused to have an inventory made, as Beneimbene the notary had advised. "I desire," so he stated to the Ferrarese ambassadors, "that the duchess shall do with her property as she wishes." He had also given her nine thousand ducats to clothe herself and her servants, and also a beautiful sedan-chair of French make, in which the Duchess of Urbino was to have a seat by her side when she joined the cavalcade.

Pozzi to Ercole, Rome, December 28, 1501.

While Alexander was praising his daughter's graciousness and modesty, he expressed the wish that her father-in-law would provide her with no courtiers and ladies-in-waiting but those whose character was above question. She had told him—so the ambassadors wrote their master—that she would never give his Holiness cause to be ashamed of her, and "according to our view he certainly never will have occasion, for the longer we are with her, and the closer we examine her life, the higher is our opinion of her goodness, her decorum, and modesty. We see that life in her palace is not only Christian, but also religious."

Pozzi and Saraceni, Rome, December 28, 1501.

Even Cardinal Ferrante Ferrari ventured to write Ercole—whose servant he had been—a letter in which he spoke of the duke's daughter-in-law in unctuous terms and praised her character to the skies.

Rome, January 9, 1502.

January 5th the balance of the wedding portion was paid to the Ferrarese ambassadors in cash, whereupon they reported to the duke that everything had been arranged, that his daughter-in-law would bring the bull with her, and that the cavalcade was ready to start.

La Illma Madama Lucrezia porta tutte le bolle piene et in optima forma. Pozzi and Gerardo to Ercole, Rome, January 6, 1502.

Alexander had decided at what towns they should stop on their long journey. They were as follows: Castelnovo, Civitacastellana, Narni, Terni, Spoleto, and Foligno; it was expected the Duke Guidobaldo or his wife would meet Lucretia at the last-named place and accompany her to Urbino. Thence they were to pass through Caesar's estates, going by way of Pesaro, Rimini, Cesena, Forli, Faenza, and Imola to Bologna, and from that city to Ferrara by way of the Po.

As the places through which they passed would be subjected to very great expense if the entire cavalcade stopped, the retinue was sometimes divided, each part taking a different route. The Pope's brief to the Priors of Nepi shows to what imposition the people were subjected.

Dear Sons: Greeting and the Apostolic Blessing. As our dearly beloved daughter in Christ, the noble lady and Duchess Lucretia de Borgia, who is to leave here next Monday to join her husband Alfonso, the beloved son and first born of the Duke of Ferrara, with a large escort of nobles, two hundred horsemen will pass through your district; therefore we wish and command you, if you value our favor and desire to avoid our displeasure, to provide for the company mentioned above for a day and two nights, the time they will spend with you. By so doing you will receive from us all due approbation. Given in Rome, under the Apostolic seal, December 28, 1501, in the tenth year of our Pontificate.

In the archives of the municipality of Nepi, where I copied the brief from the records. There is a similar letter in the same form and of the same date, addressed to the commune of Trevi, in the city archives of that place. The latter is printed in Tullio Dandolo's Arte christiána—Passeggiate nell' Umbria, 1866, p. 358.

Numerous other places had similar experiences. In every city in which the cavalcade stopped, and in some of those where they merely rested for a short time, Lucretia, in accordance with the Pope's commands, was honored with triumphal arches, illuminations, and processions—all the expense of which was borne by the commune.

January 6th Lucretia, leaving her child Rodrigo, her brother Caesar, and her parents, departed from Rome. Probably only two persons were present when she took leave of Vannozza. None of those who describe the festivities in the Vatican mention this woman by name.